By Arshad Alam, New Age Islam

20 June 2020

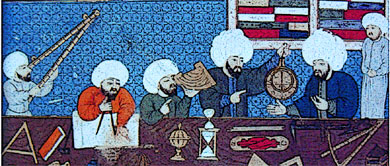

Ibn Sina, the ace scientist and philosopher of the medieval world, was a deeply religious man. It is said about him that he could master the works of Aristotle only with great difficulty. It took no less than forty attempts for Ibn Sina to decode the essence of what Aristotle was arguing. Faced with much mental agony during deconstructing Aristotle, Ibn Sina only found solace in prayers. He had no fixed time for offering his prayers: whenever he got stuck with Aristotle, he would immerse himself in remembering God. Prayers were not just therapeutic but this submission to God also opened for him newer possibilities of understanding the finer merits within Aristotelian worldview. For him, there was no separation between religion and science, both being equally valid paths to know the ultimate reality. In fact, he hardly ever thought that the two different paths leading to the same destination. For him, inquiring about essences and causes of the material world was part of doing religious work itself.

Today, Muslims make a fundamental distinction between the world of science and Islam. They think that science is about this world whereas Islam is about the eternal world and life on this earth is to prepare oneself for that eternal world. It is not a surprise then that the Muslims have hardly made any scientific contribution to the modern world. Partly, the reason has to so with our distrust of science and how some of its fundamental tenets run contrary to the teachings of our holy book. The fact remains that it was only through Ibn Sina’s commentaries that the western world discovered Greek thought which eventually led to the Enlightenment and ultimately changed the very face of Europe. Thus, modern science and philosophy do not belong to any particular religion, rather it is the common heritage of all religions. Muslims make the fundamental mistake of coupling science within a kind of ‘westernism’ which is contra-factual.

The result of this revulsion has done immense harm to the Muslim world. In the Indian subcontinent, its effect could be seen in the curriculum of Deoband madrasa. Established in 1867, this madrasa and later a school of thought, banished all of science, applied science and philosophy from its syllabus which is called the Dars e Nizami. However, this nomenclature was nothing but a fraud for the simple reason Dars e Nizami was a syllabus which predated the establishment of Deoband. It was basically a state curriculum and was taught in state supported madrasas like the Firangi Mahal at Lucknow which taught both manqulat (revealed knowledge) and Maqulat (rational knowledge). Thus, the study of law, applied science, philosophy and religion was all done under one roof. Students were free to choose a branch of study depending on their intellectual proclivities. This syllabus produced judges, court officials, architects and Ulama in equal measure.

Deoband killed the very soul of Dars e Nizami. It banished the study of all rational content from the syllabus, and substituted them with the study of Quran and Hadis, thus reducing knowledge to religious studies alone. Indeed, its founders were quite clear that rational studies only add to the ‘confusion of the mind’ and therefore there was no need of teaching either philosophy or science. This way of thinking was not just influenced by the colonial separation between the ‘religious’ and the ‘modern’ but also by the Ashari intellectuals like Ghazali who in his ‘Incoherence of the Philosophers’ had labelled such knowledge systems as ‘Kufr’. Ghazali is perhaps the most important cause why millions of Muslim children today are being brought up with a geocentric worldview.

The march of scientific knowledge has been relentless, dismantling many false gods on its way. Unable to cope up and ignore the salience of this demonstrative branch of knowledge, some Muslims devised a novel way to appropriate it and started a project called the ‘Islamization of science’. In practice, there are two ways in which this ‘Islamic science’ is being done today. The first is a very crude attempt to claim all scientific achievements as Islamic either by linking all discoveries to an Islamic influence or by claiming that discoveries by Muslim scientists were fundamental to the constitution of modern science. Largely a nostalgic attempt, this approach does not answer the fundamental dissociation between science and the Muslim mind today.

The second way to do Islamic science is to spiritualise science, which is to say that there are some truths which are not known by science and therefore one has to accept the limits of modern science. The problem with this approach is the a-priori assumption about the existence of some higher Truth which in all certainly can never be approximated by science. The other problem with this approach is that when faced with contradictory claims between science and Islam, one has to choose Islam despite ample proofs to the contrary. Ultimately, if this problem has to be resolved, then Muslims have to come terms with the fact that divine revelations may not be so divine after all. If one assumes that each and every word of the Quran is beyond doubt, then one cannot do any kind of science, far less ‘Islamic science’.

Muslim philosophers anticipated this problem long back and have argued for levels of knowledge, the most important being that branch of knowledge which is demonstrable or empirical. In case there is a conflict between the sacred text and demonstrable knowledge, then it is the latter which should be taken as the truth. To get over the problem of the divinity of sacred text, Ibn Arabi for example argued that most of the verses in the Quran were allegorical in nature which lends itself to multiple meanings and therefore one can never be sure of the real meaning which it is trying to convey. Under such circumstances, it is only prudent to look forward to logic and empiricism as sources of valid knowledge.

If only Muslims would have taken forward their earlier wisdom, the world would have been a different place today.

Arshad Alam is a columnist with NewAgeIslam.com

No comments:

Post a Comment