Farahnaz Ispahani’s book, bravely records near extinction of Pakistan’s Religious Minorities, Hindus, Christians and Jews, and focuses on intensifying sectarian conflict

By Ashok Malik

30 January 2016

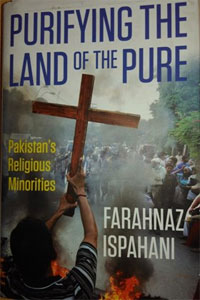

Farahnaz Ispahani’s recent book, Purifying the Land of the Pure: Pakistan’s Religious Minorities, is a detailed and extremely educative account of the tragic history of her country. A well-known political activist and writer, Ms Ispahani bravely and categorically records not just the near-annihilation of religious minorities — Hindus, Christians and Pakistan’s now extinct Jews — from the nation founded by Jinnah, but also the intensifying sectarian conflict.

She worries, as others have, that a country born as a homeland for South Asian Muslims, gradually became an Islamic nation and finally a state upholding particular interpretations of Sunni Islam. In her book, she sees Pakistan’s Shia and Ahmadiyya communities as among Pakistan’s oppressed religious minorities. This is certainly a strange paradox, given so many Shias, including the Aga Khan, were instrumental in the Pakistan movement and in financially supporting its fledgling state. As Ms Ispahani reminds her readers, Mr Zafarullah Khan, Pakistan’s first Foreign Minister and an acclaimed politician and diplomat of his times, was a proud Ahmadiyya.

The Ahmadiyya community was officially declared non-Muslim by a constitutional amendment passed by the Pakistan Parliament in 1974. This was one of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s concessions to the Islamists and, rather, than stem demands, put his Government and his country on a slippery slope. Within years, Zia-ul-Haq was in power and promoting even stricter interpretations of (Sunni) Islam, complete with blasphemy laws that discriminated against minorities and other laws that discriminated against women.

The year 1974 and the fact that a modern Parliament decided to define religious identities by classifying sects and groups of populations as belonging to or not belonging to a religion is commonly regarded as a milestone in Pakistan’s history. It is seen as the date when the singling out of the Ahmadiyya people, observant and practicing Muslims, as heretical made them vulnerable to violence and in-country exile.

However, the targeting of Ahmadiyyas was not a recent phenomenon in 1974. It dated back to the earliest years of Pakistan. “In 1948,” Ms Ispahani writes, “an Ahmadi Army officer was murdered in Quetta, near the site of an anti-Ahmadi rally … By 1953, the resentment against Hindus was supplanted by antagonism towards the Ahmadiyya sect.” In 1953, there was a mass killing of Ahmadiyyas that began in Punjab, under the aegis of the Tehrik-e-Tahaffuz-e-Khatm-e-Nabuwwat (Movement for the Protection of the Finality of the Prophet): “Its appeal to mainstream Sunni Muslims was emotive. The believers had to defend the Prophet Muhammad’s status as the final prophet of god and this could only be done by legislation declaring Ahmadis non-Muslims and by restricting their role in Government.”

The anti-Ahmadiyya riots began in Punjab in February 1953. In what Ms Ispahani describes as a “pogrom”, some 2,000 Ahmadiyya followers were killed by fellow Muslims. The Government either lost control or didn’t try too hard. The mob murdered the few policemen who sought to do their duty; most policemen didn’t bother.

In about a week, the book quotes an account as saying, “The telephone system, the railways and electrical distribution equipment were damaged and … it seemed as if Lahore might fall totally into the hands of the mob, and the Army’s assistance was requested.” Martial law was declared in Lahore, following the city’s biggest spell of violence since the Partition riots of 1947. Consider the irony. In six years, those who had “won” Lahore were fighting and killing one another.

The import of the 1953 riots is not just in the fact that they signalled the start of a sectarian blood feud among the Muslim people of Pakistan. Their true significance lies in the prescient Munir Commission report, which Ms Ispahani writes about in deserving detail. The two-person judicial commission, the “Punjab Disturbances Court Of Inquiry” to give it its formal name, was headed by Justice Mohammed Munir of the Pakistan Supreme Court. In less than a year, it produced a 387-page report, following 117 sittings, 92 of which, as the book tells us, were devoted to hearing “statements of various parties”.

The commission tackled the question of Pakistan being declared an Islamic state and what this may mean. The two judges — Justice Munir’s colleague was Justice AR Kayani, a noted jurist and civil liberties voice who suffered in later years due to his criticism of Ayub Khan’s dictatorship — were clearly concerned about the influence of religion on affairs of state. They pointed to the absence of consensus on basic definitions of Islam and Muslim identity, stressing that these were matters the Government and state would be wise to avoid.

“According to the Shias all Sunnis are Kafirs,” the commission’s report said, “and Ahl-i-Quran, namely person who consider Hadith to be unreliable and, therefore, not binding, are unanimously Kafirs and so are all independent thinkers… (as such) neither Shias not Sunnis nor Deobandis nor the Ahl-i-Hadith nor Barelvis are Muslims nor any change from one view to the other must be accompanied in an Islamic state with the penalty of death if the Government … is in the hands of the party which considers the other party to be Kafirs.”

As Ms Ispahani stresses, with her carefully chosen extracts from the report, Justice Munir and Justice Kayani were astutely and firmly establishing the absurdity of the arguments made before them. “No two Ulema,” they wrote, “have agreed before us as to the definition of a Muslim. If the constituents of each of the definitions given by the Ulema are given effect to, and subjected to the rule of ‘combination and permutation’ and the form of charge in the inquisition’s sentence on Galileo is adopted mutatis mutandis as a model, the grounds on which a person may be indicted for apostasy will be too numerous to count.”

In conclusion, the Muslim Commission made a pithy remark: “If we adopt the definition given by any one of the Ulema, we remain Muslims according to the view of that Alim (scholar) but Kafirs according to the definition of everyone else.” In reproducing that line, Ms Ispahani has said it all.

Ashok Malik is senior fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

Source: dailypioneer.com/columnists/edit/how-pakistan-played-with-secularism-creed.html

No comments:

Post a Comment